The Gadhimai festival in Bariyarpur, southern Nepal, is held every five years. The animal sacrifices are supposed to bring good fortune to the worshippers – both material and metaphysical. This event is growing in popularity, each celebration draws more participants, so more animals are sacrificed. The festival has become a priority in the eyes of Nepal’s government – a means of enhancing the community’s conditions.

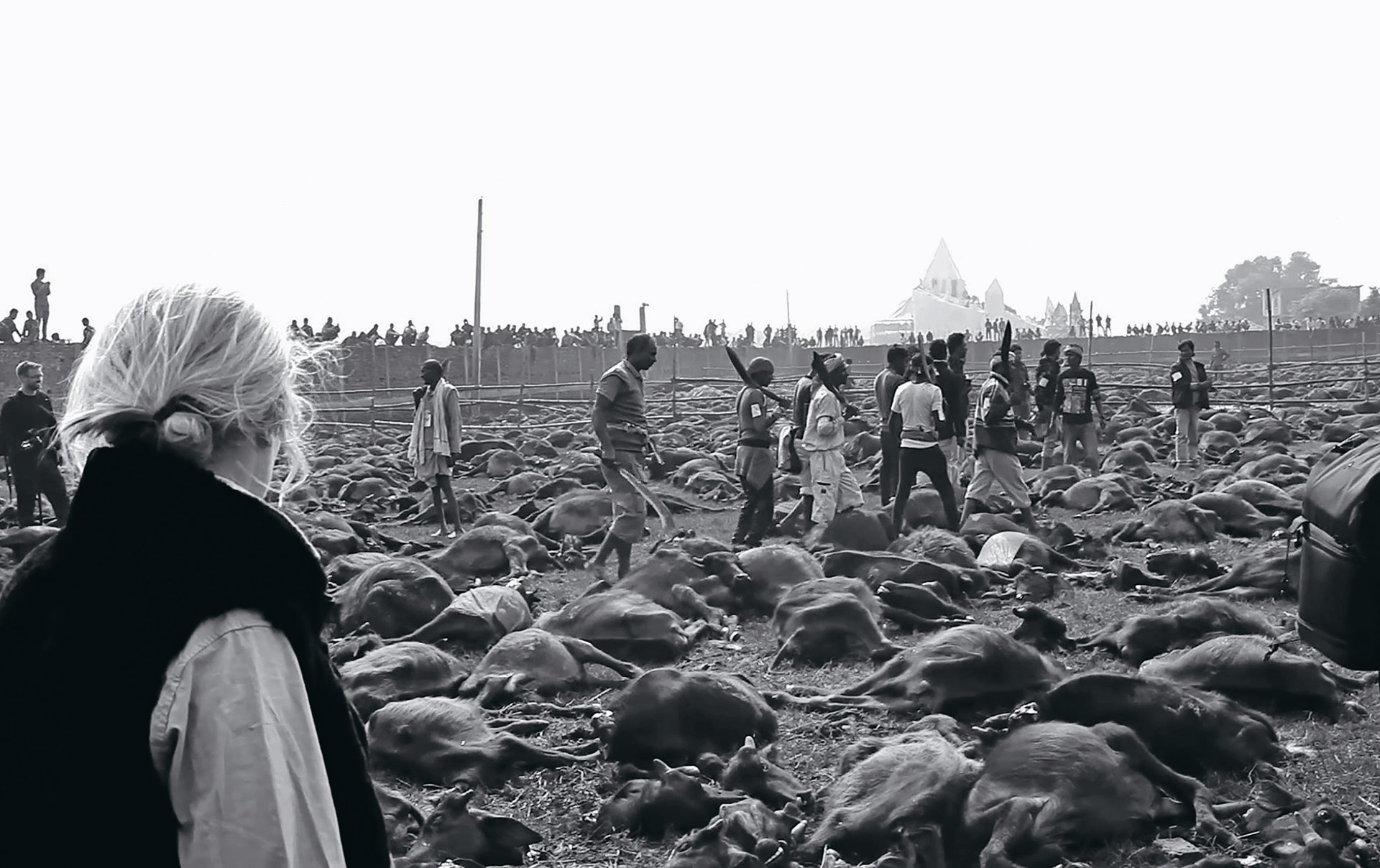

For the last several years, activists have been running a strong campaign against this festival, announcing mass turnouts, boycotts and blockades. Recently, the activists announced that a cattle transport from India would be blocked – it seemed like they were about to shut down the event. The blockade never happened, even the opposite came true: Nepal received an even bigger cattle transport. In 2016, when this video was taken, the festival reached historical numbers in terms of participants and slaughtered animals. A reporter from Nepalian television noted that, judging from the numbers, the next edition would be even bigger because the festival yields increasing benefits for the community and the administration.

This work is not an ecological critique, a reportage, a documentary, or the voyeurism of a tourist.

The festival is a straightforward and obvious way of building a community through animal sacrifices, but at the same time it stirs a vulgar thought: “What a waste!” For participants, the festival acts asa door to approaching old traditions from new perspectives; traditions that are supposed to yield concrete results – here and now. They cut off heads and witness auto-affirmation in a ritual that leads to happiness and meaning. Socially excluded1, they strive to find proof of their own lives, they want to fully dedicate themselves to the world. They are tired of feeling bitter, they want to gild their failed lives. This is the only hope for the excluded, who believe in the wheel of fortune. Expectations are gargantuan . . . and the corpses are everywhere.

Total freedom. The only achievement is gaining an advantage over the slaughtered cattle, as this slaughter lacks an emotional link between those who behead and those who watch. This strong festive expression is kitsch of a kind, tangled with a perverse desire to participate. The sacrifice exists only to give fortune an opportunity; and this fortune leaves the buffalos2 to the mercy of banality. Monotonous beheadings never get boring, it’s easy to get used to them. The consuming emptiness is conquered through a full stomach. One can also interpret this as a ritual consumption of death, with a happy end in the form of a happy spectator. Heroes are created during this “picnic,” heroes who compete in beheadings, like professional athletes. They are respected, happy to be photographed3. What’s interesting is that the event’s strength lies not in the number of beheaded cattle, or the amount of blood spilled, but in the field “covered in shit,” on which severed heads roll around – which, in its own terms, makes reporting a difficult task.

The blonde woman who appears in the work ensures a degree of moral comfort, she reduces the anxiety. There are moments, when her communication and relation with the viewer is more attractive than the “pig killing”4. She draws all attention not because – or not only because – she is a blonde, but mainly through her being an object of desire, an archetype of fortune. She is proof that everything is going well, even from a perspective of a calve that is soon to be sacrificed.

I was one of few foreigners present at the festival; the others being a couple of photographers from various countries and maybe a couple of tourists. And the blonde woman, of course. I was waiting at the festival’s veterinary stand very early in the morning and watched numerous empty boxes with labels of animal painkillers. The stand manager explained that the law requires painkillers to be used, but there is not even nearly enough of them. It is estimated that 40,000 cattle will be slaughtered, but there could be much more, if we count every animal that can be sacrificed

(even 200k).

A moment before the slaughter began, the military secured the cattle site, using a wall to separate it from the spectators (participants). At one point the situation got very tense, spectators started throwing rocks, a few soldiers were injured.

They had to step back. I was sitting on the wall, taking photographs, soldiers were constantly rushing over to me, telling me to get down. I remembered a scene from the Seven Years in Tibet movie, where Buddhist monks dug a small ditch for an electrical wire. While digging, they were diligently picking out worms from the soil and moved them to a different spot, where they were in no threat. Tibet is a long way from here.

A couple of months after the festival, Nepal was struck by the biggest earthquake in the history of the country.

1 They see themselves that way: as deficient consumers.

2 Buffalos are a symbol of social status.

3 Górka Dolna is a Slovakian TV series. In one of its episodes, a woman is admiring a boar killed in a hunt, resting in a trunk of her friend’s car. She says: “Everything that has been killed is in fashion now.”

4 After a few hours at the festival I came to the conclusion that this happening is analogous to pig killing, only it is done on a much larger scale.

My aim is not to keep the cultural industry “alive” and bringing new, finespun entertainment.

The field of conceptual actions is more important but according to my rules.

Aesthetic problems are out of my scope. I don’t care about them.